Book Review: Rage by Stephen King

Rage is one of the novels Stephen King wrote under his pseudonym "Richard Bachman." It has a theme that is common in King's early novels and short stories -- school violence. Unlike many of his other novels and even one of his other school violence novels, there is nothing supernatural about Rage. This is a story that resonates in reality. It exposes a fear that is unavoidable in modern schools.

The antagonist with a somewhat protagonistic streak in this novel is high school student Charles Decker. He is also the narrator. From the beginning of the novel -- first period of a normal day at high school -- there are hints that something is not right with Charlie. As the novel progresses, the reader learns that Charlie has a recent history of violence in the school, though all that is learned is he did something to a teacher during class. The novel follows through Charlie's recollections of the day and some flashbacks of his life. There are moments where King skillfully makes it possible to pity him, but his life just was not traumatic enough for the reader to forgive him for what he has done and what he is about to do.

Before long, Charlie has shot and killed two teachers. The bulk of Rage takes place during his standoff with the police. He has an entire classroom full of his peers hostage, so it takes several hours for the standoff to end. During that time, Charlie threatens his school administrators and the police with violence on the other children. However, most of the children do not fear him or, if they do, they do not fear him for long. Stephen King, through Decker, turns the classroom into a teenage confessional. The students take this rare opportunity where life is not mapped out for them by an endless parade of parents and teachers to say what they want to say. Throughout this, Charlie is at times fascinated and confused by them. In some ways, he is just like the rest of them, with problems no greater or lesser. There is just something in him that snapped. That thing seems to disappear over the course of the novel, but the reader knows it is still there and that this cannot end well for Charlie.

In what this reader feels was a brilliant turn on Stephen King's part, Charlie does not hurt any of the students. He keeps them around for some reason even he does not quite understand. However, he allows them to hurt each other, even encourages it. In the end, he hurt the teachers and the students hurt each other. The message seems to be that, freed from the bonds of servitude every teenager owes society, they are all Charlie Deckers. They just have a door that Charlie lacks and Charlie encouraged them to open it a little whether he meant to or not.

Sometimes, King's novels are gore fests and mind screws, peppered with poignant human moments that help anchor his fantastic stories in reality. He is brilliant at just such novels. However, there are also those novels that are all poignancy, all real, all too human for some readers' liking. Rage is that kind of novel. It is something that can happen. In fact, it is something that happens all the time. King just manages to write about it in a way that does not demonize the child ("We Need to Talk about Kevin" anyone?) or make him some bullied kid with a score to settle. It is the way he makes him an "any kid" that really hits home. King has decided to ask his publishers to stop publishing the novel, though. Several school shootings have sadly been linked to it, though saying the novel "caused" them is a stretch. Still, Stephen King is a fiction writer. Surely, it would appall him to have his fiction become a reality whether it is his fault or not.

Shelly Barclay

Book Review: The Heretic's Daughter by Kathleen Kent

|

| Accused witches at the Salem Witch Trials |

The Heretic's Daughter by Kathleen Kent is a novel about a young girl, her relationship with her mother and her part in the Salem Witch Trials. Unlike many other novels about the time, this one is an intimate look at a simple family and the ties that bind mothers and daughters. It must be assumed that much of the novel is guessing on the part of Kathleen Kent, given the scant records of anything beyond "She's a witch!" that were kept at the time. Even the best researchers are unlikely to find more than the accusations given in court, rumors and the birth/death/marriage records of the accused's family. Nonetheless, Kathleen Kent paints a believable picture of the Carrier family and the woman who Cotton Mather so disdainfully called a "rampant hag," only to be remembered in history as a superstitious fool who was partly responsible for the most infamous wrongful executions in United States history.

Martha Carrier was one of the women hanged after being found guilty by the Court of Oyer and Terminer. She, unlike so many others, declared her innocence to the very end. In fact, she is known for being outspoken and derisive of her judges and the girls responsible for the witch-hunt. She had five children, a simple farm and a life marked by the deaths of family members from small pox and the hardships that came with being a poor colonist in 17th century Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Heretic's Daughter is written from the point of view of her daughter Sarah Carrier, who was also accused during the Salem Witch Trials, though just a girl at the time.

The beginning of the novel is very much a look at Martha's character. Everything from the relationships Sarah forms with her cousin to the way she behaves at home shows Martha's personality. Sarah grows to dislike her mother, who is coarse, disciplinarian and seemingly simple. This is the picture of Martha that is also painted by history, but there is no way of knowing if the feelings of resentment felt by Sarah in the novel were actually present. It seems almost a modern view of mother/daughter relationships. There is simply no way of knowing if a simple farm girl like Sarah would have resented her mother. As the story develops Kathleen uses a bit of artistic license and begins to paint Martha as a literate and somewhat soulful woman whose callousness comes from necessity. This makes for a good story, but really we only know that she was outspoken. She was likely pleasant by today's standards, anyway.

The tragedy that befalls this family is inevitable to any reader who approaches the novel with knowledge of the Salem Witch Trials. Four of the children are taken to jail after their mother. The only family member left to fight for them is their father. Here is where the story really becomes something special. Kathleen Kent obviously took great pains to accurately describe the attitudes of the accused and their accusers. She did a magnificent job of painting Salem as in the grip of hysteria, which it was. She also did a great job of including individuals who were against the harsh conditions in which the witches were kept. In the end, the emotions she paints are believable and touching. In short, this is a great book for anyone who loves a historical fiction novel. It is as if Kent is reaching back through the centuries to point her finger at the real criminals of the Salem Witch Trials. Bravo to Kathleen Kent on creating such a moving freshman novel.

Shelly Barclay

Book Review: Madwand by Roger Zelazny

Madwand by Roger Zelazny is a science fiction/fantasy novel that I found literally tucked away in a dusty corner of my local library. It is not much of an insult to the writer, as that is where they hide all science fiction/fantasy that is not for children or young adults. Perhaps I will dedicate an article to why I think that is sometime, but for now, I am digressing. I did not come across Madwand by chance. I read a short story novel by Zelazny several years ago and have been itching to get my hands on more stuff by him ever since. The problem was, I lent the book out and the man's crazy last name made it impossible for me to find his work.

Finally, I figured out the name of the short story anthology and marched -- okay, drove -- to the library. I could not find anything in their computer and nothing in the fiction section (angry face). A few trips later, I found the dejected science fiction/fantasy section at the back of the nonfiction section (pointedly angry face). There, I found a mere three novels by this man, who has apparently written many more than that.

I grabbed one of the lonely Roger Zelazny novels and scurried away. Looking back, I am relatively certain I did not give it much of a once over. I did not want to miss my window of opportunity. You never know when the one other adult science fiction/fantasy fan in straightlacedville would show up and snatch it out of my claws. When I got home, I Googled the book and discovered that it is a sequel. Ugh. Well, I was not about to bring Madwand back to a library that a quick phone call showed did not have the first book. With that reasoning in mind, I read Madwand without the benefit of reading its precursor, Changeling. Luckily, it proved to be a decent stand-alone novel.

Basically, Madwand is about a sorcerer who was raised in a dimension without sorcerers. I am assuming it was Earth, but I will have to read Changeling to get that information. Before the start of Madwand, he returns to the world he was hidden from at birth. There happen to be many sorcerers there, but Pol -- our antihero of sorts -- was not raised to be a sorcerer, so he is a "madwand." So, we have an untrained, morally ambiguous sorcerer surrounded by other sorcerers of all ilks, dragons, deception, thieves, dwarves that live in factory/castle shells, a demon for a sometime narrator, glimpses of advanced dimensions full of nightmarish creatures and just about everything else you want from a sci-fi/fantasy novel. The best part is that Roger Zelazny is articulate. Oh, yes, you can forget about the last twenty years of pandering to middle school reading levels. Old school fantasy has literary finesse.

I get the sense that Madwand is better as a sequel. I really felt the lack of back-story as I read it. Of course, it can be read alone, as mentioned above, but I really wanted to know how Pol came to be where he was and I did not want to know from simple allusions (not illusions . . . snort) to his childhood and how he got to the world of castles and deceitful wizards. I will let you all know when I get my hands on Changeling.

Shelly Barclay

Five Classic Novels for Romance Lovers

|

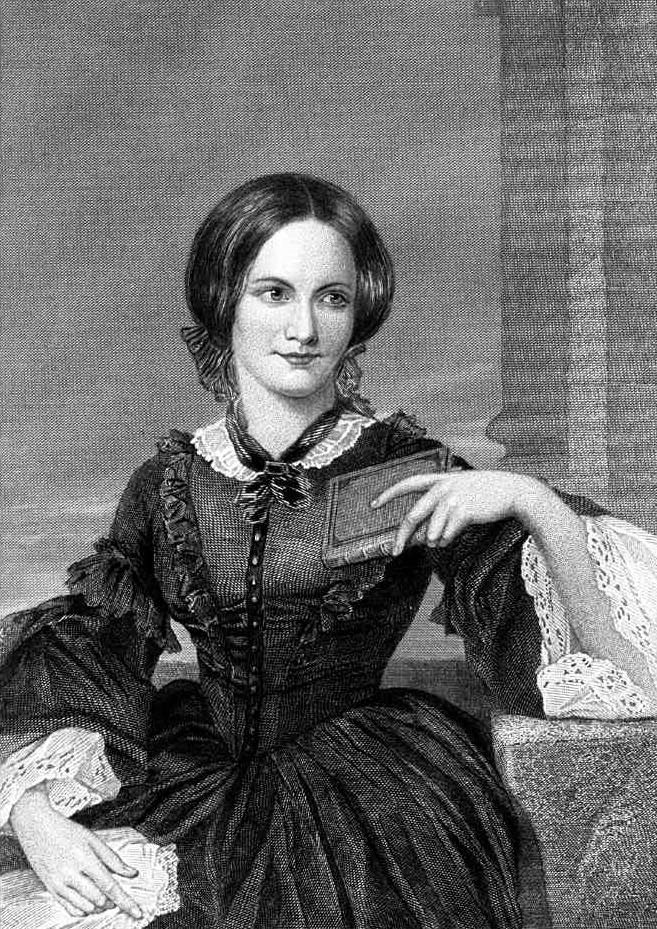

| Charlotte Bronte |

5. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald is essentially the story of a man -- Jay Gatsby -- who appears to have it all, but wants only one thing -- Daisy Buchanan. It was first published in 1925 and has remained required reading for anyone who wants to know about the evolution of American literature since. The story of Daisy and Jay is central to The Great Gatsby. However, it is the setting, the period and the other characters that make the story work. From angry mistresses to corrupt "associates," 20s style parties to tangled love affairs, The Great Gatsby has it all. Of course, dime a dozen spy novels have the same. It is simply Fitzgerald's writing and the tragic figure of Jay Gatsby that make the novel stand out among the multitudes of lesser novels.

4. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte has the distinction of being the only novel on this list that has a simple, self-sufficient, average-looking and kind heroine. Sure, some of the other women on this list have one or some of these qualities, but only Jane Eyre has all. She is the most realistic, sad and inspiring of all these women. Her love is the simplest, least greedy and most respectable of all these fictional women. She makes this novel work. She is the kind of woman you want as a friend. She is the kind of women that you want to scold men into loving. In short, she is great. There are other elements to the novel that make it worthy of a "best" list, the greatest being charity, overcoming odds and mystery. The mystery of this novel is actually quite surprising.

3. Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

Gone with the Wind, ah, I wonder how many people are irritated that this is not number one on this list. Well, Margaret Mitchell did a wonderful job of writing something that is now not only considered classic romance, but was also historical romance at the time she wrote it. As such, it contains historical flaws that cannot be overlooked by some readers. So, while her love/hate story between Scarlett and the long-suffering Rhett is good, the background story is too full of holes. Also, Scarlet is not easy to like -- at all. Nonetheless, it is a very sweeping story, so Mitchell can be forgiven her inaccuracies. Furthermore, Scarlet is so dramatic and fitting in historic fiction that Mitchell can be forgiven for trying to make a mean, ignorant Scrooge of woman into a lovable character. At least she is resourceful and not swoony like other romance heroines.

2. Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

The Bronte sisters or the "Bell" brothers, as they were known then were masters of romance. However, none of the sisters was as good as Emily. Their achievements, while great, fall far short of Emily's masterpiece "Wuthering Heights." This really is not an insult, given that nearly every novel in the genre falls short of Wuthering Heights. Unfortunately, it was the only novel young Emily was able to write before her untimely passing in 1848.

What makes Wuthering Heights stand out among the simpering masses is the nature of the lovers in Emily's book. Heathcliff and Catherine hate each other. I am not talking about in the way that silly damsels say "No, no, no." when they mean, "Yes, yes, yes." in these ridiculous cheap love novels (okay, even one novel on this list). I mean, they really hated each other. They went out of their way to hurt each other. There was no happily ever after, no, "I'm so sorry. I've really loved you all this time." They went to their deathbeds with angry obsessions of each other that passed for love in the dreary background of Bronte's "Wuthering Heights."

1. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen is widely regarded as the best romance novel of all time. Jane, who spent her life single and writing, manages to take her telltale "everything is going to be fine" style and turns it into a great love story. The novel was first published in 1813 and has stayed at the top of its class ever since. In fact, it is at the top of all classes. People simply love this book. Well, most people.

To be frank, I would have put Emily Bronte's magnum opus at number one on this list and Jane's quaint love story at number two were it not for the sheer popularity of this novel. Lizzie and Mr. Darcy are legends in literature. For me, the substance is not as profound as that of Wuthering Heights. Nonetheless, I find the dialogue and characters of Pride and Prejudice hugely amusing. Despite my preference for Wuthering Heights, I too am among the masses that love Pride and Prejudice. A certain innocence about it is lacking in Wuthering Heights. Of course, Pride and Prejudice lacks the emotional range of Wuthering Heights. It makes up for it with satire of the simplest form.

Shelly Barclay

Book Review: "Gator a-go-go" by Tim Dorsey

"Gator a-go-go" is a Serge A. Storms novel by Tim Dorsey. Those of you unfamiliar with Serge A. Storms and Tim Dorsey should know that Serge is not for the faint of heart. He is a psychopathic serial killer with a fun side, a moral side and manically obsessed side. People with a sense of humor about morality and drug use (by Serge's friends) will have no problem digesting "Gator a-go-go." People who have very strict moral compasses that do not allow laughter in the face of sadistic murder should probably look elsewhere.

In "Gator a-go-go," Tim Dorsey pairs Serge with his longtime friend Coleman. Coleman, like Serge's other friend Lenny, who is absent in this novel, is a laid back, copious drug using miscreant. He is not necessarily a bad guy. At least, he is not Serge-level crazy, but he is reckless in an often funny way. Along the way, Serge and Coleman pick up a number of companions, some students and a couple of promiscuous, drug-using women.

The main plot of the story is another fiasco that Serge manages to get caught up in and somehow make right with his inventive methods of killing evildoers and his limitless knowledge of Florida history. Tim has him in far-fetched, yet clever situations, as usual. Also as usual, there is not much to differentiate this novel from the rest of the Serge A. Storms novels. However, Serge is an interesting enough character to keep this stream of novels appealing and satisfying.

Shelly Barclay

Book Review: Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal by Christopher Moore

"Lamb" The Gospel According to Biff. Christ's Childhood Pal" by Christopher Moore is a look at the missing years of the life of Jesus Christ told through the eyes of his best friend Biff. Biff, along with most of the story, is a construct of Moore's imagination. What we know of Jesus and his actions through the Bible are maintained, for the most part. However, to fill in the years that were skipped in the Bible -- most of Jesus' life -- Christopher Moore had to fill in a very big blank. What he did with that blank was entertaining in many ways. He managed to paint Jesus in a good light while poking a little fun at Jesus, his friend Biff and some aspects of religion, particularly religion as it was before Christ's sacrifice.

Many readers are likely to find the contents of "Lamb" offensive. There is some offensive language, some offensive concepts and some fun at the expense of the man who saved humanity, according to the Bible. However, Moore makes it absolutely clear that what he writes is fiction. He is not trying to present any of the lost years as fact. He also points out the changes he made to the original story to suit his at the end of the novel. The story operates on the premise that Jesus lived and was the son of god. There is no denial of Christ. That should appease some devout readers. Believers and nonbelievers alike can enjoy the "Lamb" with just a little application of open-mindedness.

Among all of the laughs that "Lamb" offers is a sentimental undertone that is at once unexpected and fitting. Biff and Jesus -- known as Joshua for accuracy's sake, the only Jesus in the novel is a hotel worker -- have numerous conversations about the nature of sin and what it feels like. Yes, Christ is curious about sin in "Lamb," particularly intercourse, since he cannot have it. They joke with one another and about others. They journey into China and India while Biff acts as both comic relief and unwavering supporter.

Somewhere along this journey, the novel becomes less about fart and sex jokes and more about the nature of life, love, compassion and faith. The move is subtle and brilliant. The reader starts the novel either laughing or fuming and ends the novel feeling pity for the son of god and the pain he endured, not to mention the pain Biff endured. As mentioned above, respect is paid to those aspects of Jesus' life -- Biff being the obvious exception. There are no jokes while either suffers. Christopher Moore has few boundaries, but apparently making fun of a dying Christ is beyond one of them.

My humble opinion (you see what I did there?) is that "Lamb" is the greatest of all Christopher Moore novels. His use of the Bible to create this novel is ingenious. The dialogues between Biff and Joshua are brilliant. I somehow believe that people who have faith in Christ and a great sense of humor may actually feel closer to their Messiah after having read "Lamb." I could just be deluded, though. Either way, enjoy.

Shelly Barclay

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)